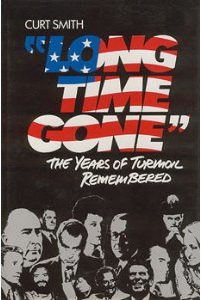

Long Time Gone

“The early 1970s once meant a call to freedom and adventure; now they evoked a strangely haunting sadness that came unsummoned, like a siren sweet postcard from the past,” writes Curt Smith in Long Time Gone (Icarus Press, 1982, 240 pages). “In the cultural collision that marked the decade’s start, the college campus was its spiritual crucible. It was a grand and awful, stirring and infuriating, lyrical and barbaric age.”

“The early 1970s once meant a call to freedom and adventure; now they evoked a strangely haunting sadness that came unsummoned, like a siren sweet postcard from the past,” writes Curt Smith in Long Time Gone (Icarus Press, 1982, 240 pages). “In the cultural collision that marked the decade’s start, the college campus was its spiritual crucible. It was a grand and awful, stirring and infuriating, lyrical and barbaric age.”

Few eras were more memorable than America in the early 1970s, when datelines included Kent State and Attica, Viet Nam polarized the nation, and Richard Nixon led it. For Smith, a member of arguably the most tumultuous freshman class in U.S. history—1969-70—the age was unforgettable—“a time,” he writes, “one might not want to relive, but would not have missed living for the world.”

A decade after graduation, Smith began to wonder how America had changed. Traveling nearly 20,000 miles, visiting Montgomery and San Clemente, Washington and New York, he talked with the men and women who gave it meaning: among them, Nixon to John Mitchell, Ramsey Clark to George Wallace, Jerry Rubin to Ronald Reagan, Betty Friedan to Billy Graham.

What ensued—their musings about the war, women’s movement, and “Silent Majority,” conflict over religion, morality, and drugs, twinned with the author’s recollections—is a poignant remembrance of right against left, hawk v. dove, Main Street against counterculture, and hard hat v. hippie. Smith writes, “What had the clashes availed them? Who in the end had won?”

America in the early 1970s warred with itself, disdaining the middle ground, where what occurred in college affected almost every person, combatants set in belligerence. In Long Time Gone, memory crests of a time when “civility and madness grappled, each bidding for the other’s soul.”